The pilot briefing is a standard operating procedure used to increase safety for flight crews. However, many airlines use outdated briefing methods that do not take into account next-generation flight decks or a modern understanding of the human brain. This guide will help you execute an effective, modernized pre flight briefing script.

Benefits of the Pre-Takeoff Emergency Briefing

Briefings help flight personnel transition from everyday life to the flight environment. Briefings are important for team building, flight preparation and leadership establishment. The briefing is also a chance to gather relevant operational data before a flight.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, inadequate preflight preparation is one of the top 10 causes of aviation accidents. A well-executed pre-takeoff emergency briefing can significantly reduce the risk of an accident occurring.

Briefing Goals

A high-quality briefing should accomplish several goals:

- Define and explain action plans and crew expectations for both normal and abnormal conditions

- Cover all subject areas to an appropriate level of detail

- Ensure all crew members understand and agree on the correct sequence of actions

- Prepare cabin and flight crew to respond to unexpected conditions

- Assign tasks

- Solicit questions and feedback

- Communicate goals to crew members and build team synergy

Problems With the Standard Pilot Briefing

Standard pilot briefings have developed several problems over decades of use:

- Too long due to years of additions

- Redundant crosschecks of automated systems

- Failure to include the pilot monitoring

- Lack of relevance to modern aviation

A study by Alaska Airlines found that problematic briefings reduced crew compliance and resulted in wasted efforts spent on executing outdated policy.

9 Safety Briefing Aviation Tips

These tips will help you create and execute a modern and effective pre-flight emergency briefing.

1. Always Do Your Briefing

Even if you have done your briefing hundreds of times, make sure you do it every time you fly, even when you are flying alone. Research shows that speaking words out loud improves memory. If something goes wrong on your flight, you are more likely to remember what to do if you speak your briefing out loud before every flight.

2. Standardize Your Briefing

Create a standard briefing that can be modified for each new airfield. Using a standard briefing reduces the risk that you may skip something. It may be helpful to organize your briefing into normal and emergency categories.

3. Start With Relevant Threats

The law of primacy says that people remember best what they learn first. Take advantage of this by putting the most important information first in your departure and arrival briefings. Begin briefings with a discussion of the relevant threats to the flight and the specific countermeasures the crew can employ if any of those threats become a safety issue.

4. Do Not Take a One-Size-Fits-All Approach

Many flight crews go through the same set of procedures for every flight, even though not all flights are the same. Adapt briefings to take into account the familiarity, proficiency, flight complexity and other factors that differ from one flight to another. Repeat your briefing before beginning the additional legs of each flight. Highlight any new obstacles or significant features of each airport and flight that your crew needs to be aware of.

5. Encourage Interaction Between the Pilot Flying and Pilot Monitoring

The pilot monitoring plays a critical role in monitoring flight safety and implementing countermeasures when safety margins are compromised. For this reason, it is important that both the pilot flying and the pilot monitoring have leadership roles in developing the content of briefings. Interactive briefings that confirm agreement and understanding between the pilot flying and the pilot monitoring after each phase of the briefing are more effective than taking questions at the end of an uninterrupted lecture.

6. Recap the Important Points

The law of recency says that people remember best what they learned most recently. Conclude your pre-takeoff emergency briefing with a recap of the critical threats and their countermeasures and the specific duties of the pilot monitoring for that departure.

7. Conduct Briefings During Low Workload Periods

The pilots need to be able to conduct the briefing while also monitoring the aircraft and flight process. For this reason, it is best to do the briefing when the workload is low enough to permit the pilots to communicate effectively while also carrying out their other duties. Before you begin your briefing, ask your pilots and crew whether they are ready to hear it.

8. Rebrief the Crew When Conditions Change

Rebrief the crew when there is a significant change in weather conditions, air traffic control clearance or the condition of the aircraft or runway. This provides an opportunity to refresh relevant sections of completed briefings and make adjustments as needed.

9. Practice Countermeasures

Go through the physical motions of any countermeasures you may need to take. This builds muscle memory which can reduce the amount of time it takes to perform the actions during an emergency.

How your aviation business can better manage flight preparation and conduct effective briefings

How To Get Buy-In on Briefing Changes

If your airline has been doing briefings the same way for decades, it may be difficult to convince leadership, pilots and crew members to make changes. Start by reviewing relevant safety data that support the changes you plan to make with stakeholders.

Prepare pilots and crewmembers for the changes several months ahead of time and thoroughly train them on both the new procedures and the reasons for the changes. Include a takeoff briefing example in your training program. Solicit feedback on the new procedures and make adjustments as needed.

Threats To Address in the Briefing

The most important component of the pre-takeoff emergency briefing is the identification and discussion of safety threats and countermeasures to take to address those threats. Some threats are unique to particular flights, while others are common.

Weather

Weather conditions can significantly impact takeoff and departure procedures. Use the information from the weather briefing conducted by the dispatcher and the most recent Automatic Terminal Information Service message. Understanding that weather forecasts are not always accurate, review local weather patterns with the crew and discuss any potential issues that the forecast does not address. Ensure that the crew takes into account the full meaning of any weather-related messages, rather than focusing on just one aspect.

Dispatch Conditions

Include factors that may affect takeoff performance and fuel consumption, such as the weight or speed of the aircraft, in your briefing. Be alert for any conditions that may not be a hazard on their own but could create a hazard when combined with other conditions. Review log book entries for information about any malfunctioning items. Allow time for repairs or replacements of malfunctioning equipment when necessary.

Takeoff Performance Limitations

Discuss prevailing takeoff performance limitations, such as the runway or obstacles. Review specific takeoff performance limitations, such as a nonstandard turn.

Weight and Balance

Review the weight and balance data from the flight plan or the final Load and Trim Sheet with the crew. Compare it to the specifications in the aircraft manual. If necessary, move passengers or cargo to maintain balance.

Wind and Runway Condition

Make sure the aircraft is on the correct runway. Confirm the runway conditions and wind so that you can respond if conditions have changed.

Rejected Takeoffs

Review the procedures necessary to make a stop-or-go decision if an engine malfunctions, you receive an air traffic control instruction to stop or a significant abnormality occurs. Make sure the crew knows which actions to take for a stop decision and which to take for a go decision. Different procedures apply depending on whether the emergency occurs before takeoff or after takeoff and at different speeds and altitudes.

Abort Point

Identifying an abort point is a failsafe that protects you if a problem with the engine or takeoff performance affects your takeoff. Choose an easily identifiable point, such as a taxiway or intersecting runway, on the airport surface that provides enough space to either takeoff or safely abort. If your aircraft is not in the air when you reach the abort point, abort the takeoff.

Emergency Landing Zones

Identify areas at and around the airport where you can land your plane safely if an emergency happens after takeoff or past the point where you can safely abort the takeoff and you can not return to your departure runway. Use software to review 3D maps of the area for fields, roads or other options.

Pre-Takeoff Emergency Briefing Process

It is helpful to break your briefing process into several smaller sections.

Pre-Flight Brief Components

The pre-flight brief includes several components:

- Information about the departure and arrival airports

- Fatigue state of crew members

- Lateral and vertical navigation

- Intended use of automation

- Status of cabin

- Discussion of takeoff and departure hazards

- Maintenance state of the aircraft

- Departure, takeoff, approach and landing conditions

- Communications

- Status of abnormal procedures

Dispatch Office

The briefing process begins at the dispatch office when the dispatcher gives the flight plan to the flight crew. At this stage, the crew makes its final decisions about the route, fuel quantity and cruise flight level.

Setup

During setup, the pilot flying and pilot monitoring ensure that everything they need for departure is ready:

- Weather reports

- Airmen notices

- Electronic flight bags

- Navigational guidance

- Instrument panels

- Relevant crosschecks

Though many standard briefing procedures include verbal crosschecks, these are generally not necessary in modern aviation environments and may reduce the effectiveness of briefings. Reserve spoken checks for critical safety information.

Brief

Once setup is complete, begin the briefing while the aircraft is at the gate or in another parking position:

- Ask the pilot monitoring to review relevant threats.

- Discuss and decide on countermeasures for each threat with the crew.

- Review the pilot flying’s plan.

- Recap the important points from the briefing.

How Fluix Can Help With Your Pre-Takeoff Emergency Briefing

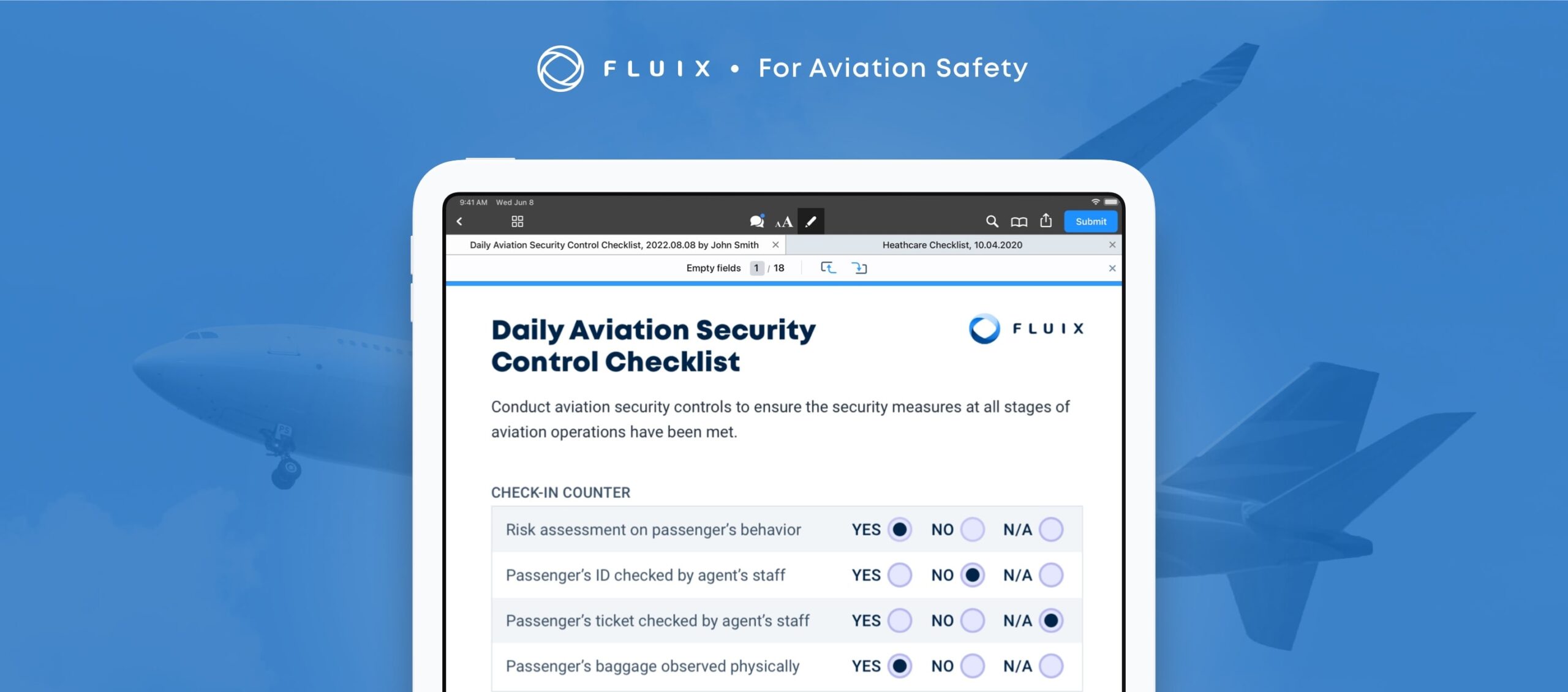

Fluix is an aviation and airline document management system that helps airlines stay safe and compliant while also reducing operation costs, freeing time for core tasks and saving man-hours. Fluix allows you to eliminate your paper binders by using an Electronic Flight Bag in the Fluix app on iPad.

This makes it easier to distribute and turnaround voyage reports, checklists, forms and other documents. The automatic syncing function of the app ensures that your crew has the latest versions of all their in-flight and aircraft ground paperwork. With offline mode, your crew can complete digital checklists even when they do not have access to Wi-Fi.